When I grow up

When asked what I want to be when I grow up, I instinctually reply with an impressive-sounding mouthful: When I grow up, I’d like to be a foreign correspondent, working in television, focusing on conflict zone journalism and war reporting.

The dream is a relatively new one, and how I plan on achieving it – and whether or not I follow through – are hazy details. But they are, nonetheless, details: Details compared with how I feel when I read and see and hear about what’s going on in the world, about human rights abuses and people getting shot to the ground over their right to stand and speak up.

It’s an anger that starts in the pit of my stomach, empties out my mind and mobilizes my feet so that in a matter of minutes, I’m storming around my house in an anxious rage. As time passes, the feeling eventually wears off. But I never forget, and to this day, am able to cite three queasy memories as my reasons for wanting to do what I want to do.

The first was back when I was in high school: I was at home and saw, for the first time, the photos of the 9/11 attacks. Specifically the ones where innocent American civilians were jumping from the second tower.

The second instance was a video of a woman, covered completely head-to-toe, getting stoned to death.

And most recently, I clicked a photo on Twitter before reading the caption. Turns out, to my horror, it had been captioned something like “what a suicide bomber looks like after detonation.”

More detail would be unnecessary. I also think it’s pretty clear how much impact these images can have on someone, psychologically, emotionally, even physically, for those with a weaker stomach than I.

There are dozens of reasons why I’m drawn to conflict zone reporting, and there are hundreds of reasons why I shouldn’t pursue it in any way other than occasionally clicking on the odd photo. But the truth is, I only need three: Three reasons that can’t be unseen, unthought, or unfelt. And once you’ve felt a certain way, it’s practically impossible to try to lead a life feeling any differently.

The future of television?

Another short post, because I’m back to school and still mentally digesting my morning statistics class. (Here’s a math equation for you: Statistics plus a 10 a.m. class, to the power of three weeks vacation with no classes or work, equals what?)

Yesterday I tweeted a New Yorker article about YouTube’s plans for cable-like niche channels, and I got to wondering whether the future of television lies in the hands of Google.

Of course, the question of TV’s direction is a little less simple than that. Cultural and generational tendencies will have, and have had, an impact on the original Tube.

To quote the article by John Seabrook, “‘The Cosby Show’ was the last TV series to command a mass following,” with over 30 per cent of all households with televisions tuning in to watch the 1985-86 season. In comparison: “Last year, ‘American Idol,’ the most popular show on TV today, pulled in fewer than nine per cent of all television viewers in the U.S.”

That’s less than a third, and just 25 years later: A trend is clear.

But here’s another potential factor, that places the future of broadcasting in the hands of 7-16 year olds.

A BBC article from yesterday cited the new annual Childwise monitoring survey that found that 61 per cent of kids and teens aged seven-16 have a phone with internet access.

The story stated that the “biggest trend in children’s use of gadgets, according to the report […] is the growth in internet use through mobile phones.”

In addition: “Children are now more likely to play with their mobiles than watch television.”

But how children are using their phones may have an even more influential sway on television’s future: Namely, is there a clear shift away from the consumption of TV content to social media and online content, or is TV content also being watched on the net?

Things to ponder, especially for someone wanting to go into television.

And now, back to statistics.

Sample investigative journalism

A short post with a link to a considerably lengthier research piece I wrote for last semester’s investigative journalism course.

In brief: The article used the then timely Attawapiskat crisis as a starting point to look into the condition of First Nations housing across Canada.

Sources include various Canadian media, Statistics Canada, B.C. Stats, RIIC.ca, J-Source, Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada.

Read by clicking on the link below:

A weak financial foundation underscores First Nations housing crisis

To have an opinion

To have an opinion, or not to have an opinion: A question that has governed my actions – or lack thereof – for quite some time.

More accurately, I’ve struggled with whether it’s important to voice an opinion.

Are our thoughts pulled out of us by others’ interest in what we have to say, or pushed onto unsuspecting listeners because we want them to hear what we have to say?

A field producer I once had put it best: “Opinions are like assholes: Everybody’s got one.”

It stuck with me.

In general, I’ve kept my opinions to myself. Mostly because I don’t feel like I really have any right to blab about things I don’t fully understand just because I have a constitutional right to blab. (I also like to think-out what I’m going to say before I actually say it.)

But today, I’ve decided to have an opinion. Or more accurately, I’ve decided to voice it.

I’ve spent the past several hours re-reading a column on columns by National Post’s Andrew Coyne.

I think he summed up the whole business of opinions nicely, stating bluntly that “nobody owes you the two minutes it takes to read your column.”

How true. And in an age of immediacy and choice and options, one could say that nobody really owes you two minutes for anything. Whether that’s called being autonomous or being careless, I’m not too sure.

Regardless, the second blow: “You do not do the reader a favour by writing something for him to read. He does you a favour by reading it.”

Also true: If you aren’t liked or read or respected or hated by some sort of sizeable audience, you’re losing. And not only that, but you’re losing to YouTube videos of pandas sneezing.

Enough said.

It’s a vicious cycle, whereby a columnist has to write to a specific audience to capture that audience. Eventually, hopefully having attracted a great enough number of readers, he can eventually transition to writing about what he wants.

The kicker, as pointed out by Coyne, is that if the audience stops liking what they read, nothing is preventing them from flipping the page. That opinion-writers’ readers have opinions about their columns is expected. But that they can altogether choose to tune out the other side of a topic is argumentatively unfair.

And that, I’ll argue, is the problem with media: That it’s so easy to tune out.

Of course this can be a good thing, because “media” includes advertising and OK! Magazine. But opinions and entertainment aside, the real problem is that good journalism is also optional.

A question: Is it not a problem that an article about alleged human rights abuses by Canadian mining companies in Africa can be ignored, because a reader simply doesn’t fancy being woken up by anything other than the morning coffee?

Whose fault is it that when “favours” are being handed out, important pieces of journalism can be overlooked? Is it the responsibility of the reader who actively chooses what to read, or the responsibility of the journalist to persuade people to care? Furthermore, what and who defines “important”?

That’s the irony, that we have a constitutional right to not practice our constitutional rights: That we can not only hold a particular view, but that we can decide to shut out all other arguments that may have had the potential to persuade us otherwise.

I suppose the problem is that this isn’t even a problem at all: It’s just a matter of opinion.

Coyne wrote also that “as a rule, most of us don’t like to be shouted at” and I have to agree, so I’ll stop shouting.

But in my “opinion,” people could stand to be shouted at a little more often if what’s being shouted merits being heard.

My first story

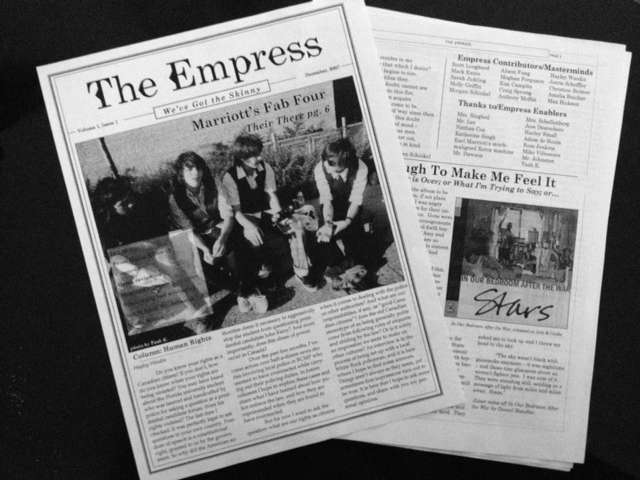

In my New Year purge of papers and knickknacks and clothes I never wear, I found a copy of my very first article, dating back to December 2007.

It was a human rights column written for my high school paper The Empress, inspired by the all-too-familiar Robert Dziekanski case splashed across the pages of real newspapers at the time.

But on the topic of “real” publications: I think the paper we put out was a more-than-decent product given that our school didn’t have a journalism class at the time. (In hindsight, it was more the teenage equivalent of a Vancouver cultural mag than a newspaper.)

I usually cringe when I read anything I wrote in high school: It’s always less imaginative than what I conjured up in elementary school, and less grammatically correct than what I write now. Hopefully.

But this piece was worth a read, and so escaped my toss pile.

Plus, it made the front page, so I had to keep it for hubris’ sake. And also because I’m fairly certain that this is the only high school story I wrote. (I never interviewed that policeman.)

—

Column: Human Rights Hayley Woodin

Do you know your rights as a Canadian citizen? If you don’t, how do you know when your rights are being violated? You may have heard about the Florida university student who was tasered and handcuffed by police for asking a question at a presidential candidate forum. Were his rights violated? The last time I checked, it was perfectly legal to ask questions in your own country. Freedom of speech is a constitutional right, granted to us by the government. So why did the American authorities deem it necessary to aggressively stop the student from questioning presidential candidate John Kerry? And more importantly, does this abuse of power occur in Canada?

Over the past few months, I’ve come across over half-a-dozen news stories involving local police or RCMP who seemed to have overreacted while carrying out their policing duties. In future columns I hope to explore these cases and share what I have learned about how police enforce the law, and how they are reprimanded when they are found to have overreacted.

But for now I want to ask the question: what are our rights as citizens when it comes to dealing with the police or other authorities? And what are our responsibilities, if any, as “good Canadian citizens”? Does the old Canadian stereotype of us being generally polite come from following rules of etiquette and abiding by the law? Or is it solely an impression we seem to make on other cultures? An interview is in the process of being set up with a local White Rock policeman, and it is here where I hope to find some answers. Things aren’t always as they seem, yet sometimes first impressions turn out to be true. It is here that I hope to ask more questions, and share with you my personal opinions.

Patenting DNA

Comparing mainstream and independent media content led me to AlterNet, and this article about private corporations patenting human genes and bodily tissues.

All I can say is that I’m glad I read it earlier in the afternoon: It’s unbelievable enough to get the mind wandering, and terrifying enough to give anyone nightmares.

The article is several weeks old, but still relevant nonetheless: It also goes hand-in-hand with point 14 in my previous post’s list about the Top 25 underreported stories in Canadian media from 2010-2011.

In a nutshell: Because the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that it is possible to patent living things, Big Pharma has for years been acquiring a monopoly on human gene and tissue patents for the purposes of research and the development of new drugs. This means independent research teams cannot work on patented genes without the consent of the patent-owning corporations, or without paying a hefty fee.

The consequences of this are definitely worth thinking about.