The people you meet

If there is one thing in common across all of the characters you meet while traveling, it’s that everybody has been somewhere. Whether it’s the Neapolitan pizzeria with a two-hour wait for the original thing, the hidden gem-of-a-beach littered with Indiana Jones-style ruins, that place in Rome – “you know the one” – or the local deli that shuts down mid-day. Sometimes it’s the end of the street; sometimes it’s the tourist hotspots: The nearest big city, or three-dozen countries around the globe. Everyone has been somewhere, and will at some point have somewhere to go.

Everything I didn’t see at the Vatican

Photos from Poland

A detour out of town

If grey were an emotion, it would probably be dread.

And everything in the vicinity was grey.

The mist, the air, the sense of numbness that gripped shivering limbs and clouded weary minds.

The fog was a smoke that lingered around the corners of the 28 buildings. They lined the rough and sandy pavement like numbered tombstones; two stories each and crumbling after six decades of remembrance. Today they see many visitors, but no one ever brings flowers.

The trees just outside of the barbed wire fences were spidery patterns, drawn with burnt charcoal on a blank slate of a sky. While everything in sight looked bleak, worn and used, no amount of time would be able to wash away the grey that permeated the decaying walls, the shattered windows, the creaking slats between the wooden barrack roofs.

The red bricks were dull and the grass was frosted. It was as though colour was an afterthought, a desperate attempt to breathe some life into the unforgiving scenery normally known through black and white photographs.

The clouds huddled together against the biting bitter wind, refraining from crying on the cold, hard ground.

Auschwitz.

Just an hour on a bus from the already faded pastel facades of Rynek Glowny, Krakow’s main square. Even after suffering through two world wars, the architecture in Poland’s second largest city is virtually untouched.

But when the Nazis came, the country could not, and did not, put up a fight. It wasn’t long until the bricks from the buildings on the city’s outskirts were taken out of the homes of Jewish residents, and put into new infrastructure for the same people.

Over a million Jews, Poles, Soviets, and Roma people were exterminated at one of the very few camps specifically designed to be a final destination: The entire population of Manchester exterminated, twice over.

Today, the Birkenau camp remains as a field of ever-increasing ruin and rubble. Two black strokes, heading toward death in parallel, enter and stop abruptly, literally at the end of the line. After decades of time and weather taking their toll, what surrounds the rails now is what is left of the nearest barracks: A single brick furnace per unit, attached to nothing but the ground that bears it.

Off in the distance is a group of two-dozen Israeli-Jewish travelers, chanting in Hebrew around a modern art monument. A smooth black sculpture void of any detail, it represents the final moments of life in the barren gas chambers. Jagged pale grey stones no bigger than two-pound coins cover its surfaces, traditional Jewish tokens of respect. They are placed haphazardly, as if dropped by birds flying over the desolate camps.

There were no birds, though. The swallows and martins singing elsewhere were nowhere to be seen. The trees were barren, and the wind blew forcefully as if trying to command attention without emitting a single moan. The lack of natural sound engulfed the site in a quiet sense of hesitation.

As the songs from the young men and women clad in black rang out mournfully to no one in particular, there were only two other sounds that could be heard.

The first, the thudding of heavy feet on gravel, mixed with sand, packed from being well-tread. The second, the Polish woman whispering nightmares into the ears of tourists and visitors.

“To survive in Hitler’s Germany…”

Her words speak truths, listing facts and figures as though she was reading an aftermath report of the damage done: Cold, emotionless, clinical.

It is the shoes – the hundreds of thousands of shoes – that visualized the impact of her account. There are babies’ shoes that, at one time, were most likely white, dainty, and worn by a girl who could not yet walk; there are formal women’s shoes with leathery straps and a wooden heel an inch-and-a-half high; there are the shoes of men who could do nothing to protect their families. Once worn by unsuspecting people, the shoes are now faded grey symbols of the Holocaust’s atrocities, preserved behind glass in one of the camp’s exhibitions.

Just outside, behind the thick brick walls that are too high to scale even with a helping hand, bodiless voices float up and over the spiked black wires that crown the fences. There’s chatter, and there’s laughter, as packs of tourists with cameras and grumbling bellies board buses with navy blue padded seats back to Rynek Glowny, and away from Auschwitz.

People came to remember, so that they could try to forget.

36 hours in London

You can learn a lot in 36 hours.

It’s the act of being fully immersed in something new that pushes you cleanly right out of your comfort zone, and lands you – rather messily – into a form of survival mode that is in constant conflict with the wanderlust of the traveler, and the curiosity of the journalist. For all three of these reasons, my eyes are wide open, and have taken in a lot on my weekend trip to Shoreditch, London.

Yesterday morning, I caught the 6 a.m. train from Preston to London Euston, a station I was warned would be completely overwhelming.

It was. But I am adamant that people at any sort of information booth, whether they want to or not, are going to help me find where I need to go. (It helps having a foreign accent, too.) The girl who helped me was lovely, and after studying and re-studying my tube map, I’ve finally understood the difference between the rails, the underground, and the overground.

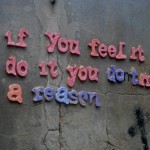

So, after taking the underground, I found myself in what I would describe as London’s “gastown” (although really, Gastown should be called Vancouver’s Shoreditch). The area’s crumbling buildings have been revived with artistic graffiti that beautifies the hip, trendy shops.

I was headed to the Rich Mix cinema for a two-day documentary film fest. With my “superpass,” I was allowed to see any of the films I wanted, attend any of the panels, and watch any of the private screenings in what was dubbed the Delegates Lounge.

I soon learned that as badly as I wanted to take in as many features as I could, I have a low threshold for how long I’m able to sit in dark rooms.

Bahrain: Shouting in the Dark, Pink Saris, and The Yes Men Fix the World were the ones I watched yesterday. The first being my favourite, the third being incredibly quirky but overall a good laugh. I attended one of the two-hour sessions that boldly asked what the differences, or lack thereof, are between documentarians and journalists to a brilliant roster of panelists, including the director of Pink Saris; the commissioning editor for major series, specials, and discussions at Al Jazeera English; the managing editor of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism; a talented journalist whose documentary on Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields was nominated for the 2012 Noble Peace Prize.

Between the Lines, so far, has proven to be worth the daunting trip. It’s inspiring and, as its tagline of “breaking boundaries in documenting the world” suggests, norm-challenging.

After my first day, I asked the woman at the reception desk if she could give me directions to the cheap hotel I’d (proudly) found and reserved online. She kind of politely refused, explaining that walking through the Roman Road ghetto is probably not something a wide-eyed chatty white girl like me (she didn’t say this, but I swore her eyes did) should be doing in the dark.

So I’m writing this long-overdue post from the comfort of a Premier Inn with a view of the city.

Needless to say, it hasn’t been a cheap weekend. But you live, and you learn. And the two biggest things I’m taking away from this quick jaunt are that 1) while I may not make the best decisions right out of the ghetto, I’m very capable of finding solutions (or finding someone who can find solutions) and being resourceful; 2) I’m enormously excited at the prospect of working in film and television.

Day two, here we go.

PS – Hi Grandma.

Carpe diem

Picking up where I left off last post, I spent the Sunday after ringing in the Year of the Snake with a trip to Manchester. For someone who had never previously been to a Chinese New Year celebration, I would say I’ve done pretty well this year, tallying one festivity, and doubling that number the next day.

When I first arrived in Preston, I took a taxi from the rail station to my flat, partially because a full day in transit had made my luggage unbearably heavy, partially because I had no idea where I was.

I’ve realized since that the trains are a short 15-minute walk from my place. After a quick 40-minute scenic tour of grassy hills, covered in sheep and black spidery trees, I was in a real city.

I fell in love with Manchester the moment our train entered Victoria Station. Half of the buildings in the city are historic, weathered with age, and architecturally beautiful. The other half are modern, avant-garde compared to Vancouver standards. It’s almost like being in a miniature display one might find in a museum: The contrast inherent to the city is itself a form of art.

Had it not been a miserably cold and wet day, I would have brought along my camera. Unfortunately, I’m still in that new-purchase phase, where I’m extra cautiously trying to avoid subjecting my camera to the tiniest scratch or speck of dirt.

But there’s no doubt I’ll be going back.

I took the trip with two new friends who are studying at UCLan for the year, both of whom are from Spain. One had to take photos of the city’s Chinese New Year festivities for a class, so off to Chinatown we went.

We saw dragons, we heard music, we braved the crowds and the rain and eventually took a break to warm up in an English pub. I had the classic fish and chips, which came with the typically British “mushy peas” that, although looking like baby food, tasted not too bad.

After wandering around a bit more, we chatted about the differences between Spain and Canada, about education, and stereotypes, over coffees and cakes until it was time for the fireworks. It was a perfect end to the weekend.

The next day – back to reality. Well, my reality: A class I enjoy that starts at two in the afternoon, and a random eco-friendly rickshaw ride to get me there. Carpe diem.

PS – Hi Grandma.